In a new study, researchers from Norway used 3D printing and low-cost parts to create an inexpensive hyperspectral imager that is light enough to use onboard drones. They offer a recipe for creating these imagers, which could make the traditionally expensive analytical technique more widely accessible. In Optics Express, they detail how to make visible-wavelength hyperspectral imagers weighing less than half a pound for as little US $700. They also demonstrate that these imagers can acquire spectral data from onboard a drone.

“The instruments we made can be used very effectively on a drone or unmanned vehicle to acquire spectral images”, said research team leader Fred Sigernes of University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS), Norway. “This means that hyperspectral imaging could be used to map large areas of terrain, for example, without the need to hire a plane or helicopter to carry an expensive and large instrument.”

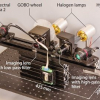

A desktop 3D printer greatly eased the process of making the custom optics holders needed for the imagers. “Making items in metal is time consuming and can be very expensive”, said Sigernes. “However, 3D printing with plastic is inexpensive and very effective for making even complex parts, such as the piece needed to hold the grating that disperses the light. I was able to print several versions and try them out.”

The hyperspectral imagers created by the researchers employ the push-broom technique, which uses precise line-scanning to build up a spectral image. The researchers added a stabilisation system to the setup so that a drone’s movement would not distort the image as it was being generated.

“Push-broom hyperspectral imagers typically require expensive orientation stabilisation”, explained Sigernes. “However, you can now buy very inexpensive gyroscope-based, electronically stabilising systems. The advent of these new systems made is possible for us to make inexpensive hyperspectral imagers.”

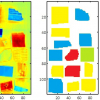

The researchers made several prototypes by using 3D printing to create plastic holders that precisely position small, lightweight commercially available cameras and optical components. They tested one of the instruments onboard an octocopter drone equipped with a two-axis electronic stabilising system. The hyperspectral imager performed well and was able to detect landscape features such as vegetation and bodies of water.

These feasibility tests showed that 3D printing is accurate enough to produce prototype parts for optical systems. The printed plastic parts were light weight and strong enough to keep the overall system light and small, which is important for use with drones. After testing, metal versions of 3D printed parts could be ordered if desired to create imagers that would be more durable.

Although the new imagers do not provide the sensitivity of traditional hyperspectral imagers, their performance is sufficient for mapping terrain or detecting ocean colour in daylight. The researchers are now working to improve sensitivity by making slightly larger versions of the instruments that would still be small and light enough for use on drones. Improving the sensitivity of the imagers will provide higher quality data.