Attosecond laser pulses in the extreme ultraviolet (XUV) are a unique tool enabling the observation and control of electron dynamics in atoms, molecules and solids. Most attosecond laser sources operate at a pulse repetition rate of 1 kHz, which limits their usefulness in complex experiments. Using a high-power laser system they have developed, scientists at the Max Born Institute (MBI) have managed to generate attosecond pulses at 100 kHz repetition rate. This enables new types of experiments in attosecond science.

Light pulses in the extreme ultraviolet (XUV) region of the electromagnetic spectrum, with durations on the order of 100s of attoseconds allow scientists to study ultrafast dynamics of electrons in atoms, molecules and solids. Usually, experiments are performed using a sequence of two laser pulses with a controllable time-delay between them. The first pulse excites the system, and the second pulse takes a snapshot of the evolving system, by recording an appropriate observable. Usually, the momentum distributions of ions or electrons or the transient absorption spectrum of the XUV pulse is measured as a function of delay between the two pulses. By repeating the experiment for different timings between the two pulses a movie of the dynamics under study can be created.

In order to get the most detailed insights into the dynamics of the system under investigation, it is advantageous to measure the available information about the time evolution as completely as possible. In experiments with atomic and molecular targets, it can be advantageous to measure the three-dimensional momenta of all charged particles. This can be achieved with a so-called reaction microscope (REMI) apparatus. The scheme works by ensuring single ionisation events for every laser shot and detecting electrons and ions in coincidence. This, however, has the drawback that the detection rate is limited to a fraction (usually 10–20 %) of the laser pulse repetition rate. Meaningful pump–probe experiments in a REMI are not possible with 1 kHz class attosecond pulse sources.

MBI has developed a laser system based on optical parametric chirped pulse amplification (OPCPA). In parametric amplification no energy is stored inside the amplification medium, therefore, very little heat is generated. This enables the amplification of laser pulses to much higher average powers than with the current “work-horse” Ti:Sapphire laser, which is most often used in attosecond laboratories around the world. The second advantage of OPCPA technology is the ability to amplify very broad spectra. Our OPCPA laser system directly amplifies few-cycle laser pulses with durations of 7 fs to average powers of 20 W. This is a pulse energy of 200 µJ at 100 kHz repetition rate. They have used this laser system previously to successfully generate attosecond pulse trains.

In many attosecond experiments it is beneficial to have isolated attosecond pulses instead of a train of multiple attosecond pulses. To enable the efficient generation of isolated attosecond pulses, the laser pulses driving the generation process should have pulse durations as close as possible to a single cycle of light. This way the attosecond pulse emission is confined to one point in time leading to isolated attosecond pulses. In order to achieve near-single-cycle laser pulses they have employed the hollow fibre pulse compression technique. The 7 fs pulses are sent through a 1 m long hollow waveguide filled with neon gas for spectral broadening. Using specially designed chirped mirrors the pulses can be compressed to pulse durations as short as 3.3 fs. These pulses consist of only 1.3 optical cycles.

The 1.3 cycle pulses are sent into an attosecond beamline developed at the MBI. The main part of the energy is used to generate isolated attosecond XUV pulses in a gas cell target. After removal of the high power NIR beam, spectral filtering and focussing, around 106 photons per laser shot (corresponding to an unprecedented photon flux of 1011 photons per second) are available for experiments.

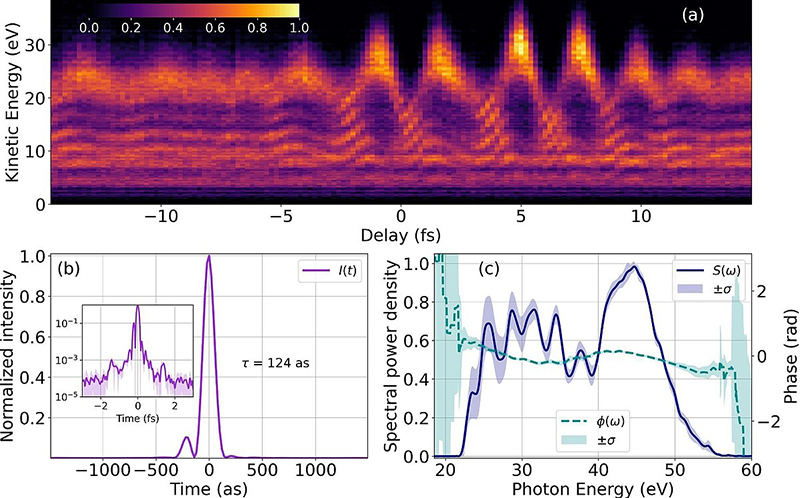

In order to characterise the generated attosecond XUV pulses, they performed an attosecond streaking experiment. Essentially the XUV pulse is used to ionise an atomic gas medium (neon in this case), while a strong NIR pulse is used to modulate the XUV generated photoelectron wavepackets. Dependent on the exact timing of the XUV and NIR pulses, the photoelectrons are accelerated (gain energy) or decelerated (loose energy) leading to a characteristic “streaking trace”. From this data matrix the exact shapes of both the NIR pulse, as well as the XUV pulse can be determined. The attosecond pulse shapes are retrieved using a global optimisation algorithm developed for this project. Careful analysis shows that the main attosecond pulses have a duration of 124 ± 3 as. The main pulse is accompanied by two adjacent satellite pulses. These stem from the attosecond pulse generation half an NIR cycle before and after the main attosecond pulse generation. The pre- and post-pulse satellites have a relative intensity of only 1 × 10–3 and 6 × 10–4, respectively.

Attosecond streaking results. (a) Measured photoelectron streaking trace. (b) Intensity envelope of retrieved isolated attosecond pulse (inset: the intensity profile on logarithmic scale) (c) Retrieved spectral intensity and spectral phase.

These high flux isolated attosecond pulses open the door for attosecond pump–probe spectroscopy studies at a repetition rate 1 or 2 orders of magnitude above current implementations.